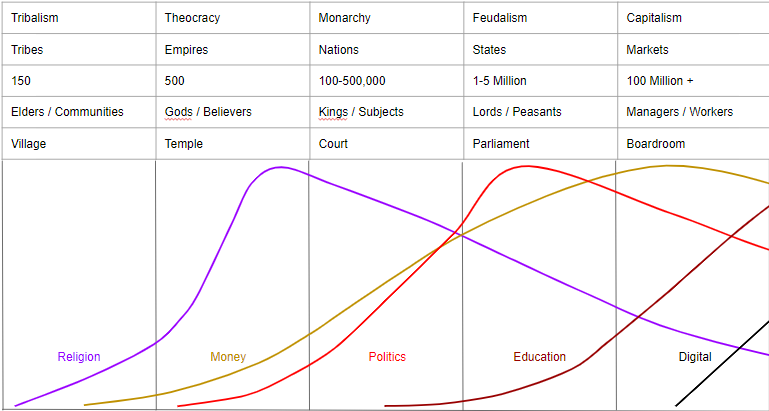

The history of human society is shaped by the history of human coordination. Over time, successful societies have evolved beyond the biological limits of unassisted human coordination (the Dunbar number of 150 people) which has necessitated the invention of collaboration technology to coordinate, control and coerce competing communities. It might be possible to map, as below, the phases of societal coordination with the prevailing dominance of the different collaboration technologies used and the governance modes and power brokers and subjugated classes that they formed.

The diagram presents a structured overview of societal development across different governance modes, detailing their corresponding social structures, settlement types, population sizes, and dominant technologies. It maps out five distinct phases: Tribalism, Theocracy, Monarchy, Feudalism, and Capitalism.

Each phase is associated with specific social roles (like Elders/Communities for Tribalism, Gods/Believers for Theocracy, etc.), types of settlements (ranging from small settlements to offices in urban centres), and working population cluster sizes that increase significantly with each phase. Additionally, it highlights the primary technology or driving force of each era, such as religion in Theocracy and money in Capitalism.

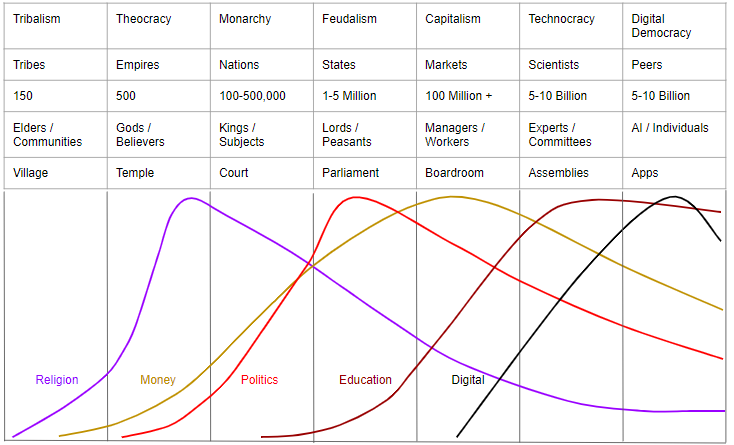

Future phases would likely be influenced by technological advancements that facilitate greater participation and efficiency in governance processes, and by a growing demand for transparency and direct involvement in political processes by the general population. To speculate on future phases, we can consider trends in political, technological, and social development:

Phase 6) Technocracy: In this phase, governance might be characterised by the rule of experts or technocrats—individuals who are specifically skilled in vital areas such as science, technology, economics, and other specialised fields. Decision-making could be heavily influenced or determined by data-driven approaches and technological solutions to societal problems. This phase reflects a shift towards rationality and expertise in governance, where decisions are made based on empirical evidence and specialised knowledge.

Phase 7) Networked Democracy: Reflecting further decentralisation, this phase could involve a highly interconnected and participatory form of governance. Technology, especially advancements in communication and artificial intelligence, enables a more direct form of democracy. People could participate directly in decision-making processes through digital platforms that allow for real-time feedback, policy voting, and decentralised consensus mechanisms. This mode might be termed Digital Democracy, where power is extremely decentralised, and governance structures are fluid, based on the participation of all involved rather than on hierarchical leadership.

The Transition from Capitalism to Technocracy

The fifth phase, Capitalism, is where we are today. Without going into the weeds of its detractors and beneficiaries, it is perhaps unique among phases in that its relentless hunger for energy has led to the creation of at least two potentially species-annihilating developments: nuclear weapons and fossil fuels. While the first has been contained through the use of political coordination (treaties and the international world order), the second seems more intransigent as the dangers it poses (climate change and pollution) are a direct result of the enhancements it provides to the world (fuel, fertiliser and plastics). This means that while the technical solution is obvious (stop or minimise the use of fossil fuels), achieving it runs counter to the interests of the ruling class which has a vested interest to resist any transition from this phase to the next one. In fact the governance system for the capitalist phase, representative democracy, is a system designed to sell capitalism to the electorate not to fairly represent the informed and authentic will of the people.

Capitalism, and particularly late-stage neoliberal capitalism, is hard-wired against any governance transition. The drive for financial growth which is its primary motivating factor creates a lethal competition to extract and exploit resources (both material and labour) in opposition to all forms of governance including limits, regulations and treaties (see the failure of the COP process). Despite the clear and unchallenged evidence that Capitalism is killing itself, it cannot pull itself out of its own doom loop. Perhaps the only consistent voice against this species suicide are scientists who embody the core ruling class of the next phase of governance: Technocracy. We must hope that the voice of science will cut through perhaps by taking advantage of the enhancements of artificial intelligence (by both the messenger and the audience) which might be able to accelerate the education of the ruling class in time to create a sympathetic ear to the plight of the world. They will only relinquish power if the threat becomes so extreme that there is no alternative, which is how Capitalism will inevitably give rise to Technocracy.

In a Technocracy, experts such as scientists and engineers, who make decisions based on data and scientific principles lead governance. While this focus on expertise may be necessary to steer societies towards a sustainable economy, it can potentially reduce public influence and concentrate power, raising concerns about authoritarian tendencies. To mitigate these issues, incorporating mechanisms such as cooperatives and sortition to select ordinary people for decision-making bodies could be vital. This method would integrate public perspectives directly into the governance process, ensuring a broader representation and preventing the over-concentration of power among technical elites. Such chambers of power, chosen randomly from the populace, can provide necessary checks and balances by injecting diverse, real-world viewpoints into technocratic decision-making frameworks. Previously adversarial nations and states will be forced to concede the irrationality of competition over finite resources and learn to cooperate transparently and work to remove individual and group inequalities.

Sortition is an example of participatory democracy which is indicative of the direction of travel into the final phase of governance: digital democracy. Although the crises affecting capitalist society can only be addressed by the handing of power to experts under a Technocratic governance structure, once resolved this must give way to a more democratic form of governance. The ubiquity of digital access and the universal availability of high quality education enhanced by (suitably constrained) AI assistance will enable an appropriately informed public to govern themselves directly through the use of digital platforms. The last foreseeable phase establishes a form of true participatory digital democracy in which cooperation is built into the system and operates to address unstabling inequalities in real time.

The full sequence of these governance modes described above is shown below.

Conclusion

This post explores the evolution of governance systems in response to the expanding needs of human societies. It traces the development from simple tribal structures to complex forms like technocracy and anticipates a future shift towards digital democracy. The narrative emphasises how each phase of governance is closely linked with collaboration technologies that have historically enabled societies to surpass the Dunbar number, facilitating larger and more complex social organisations. The document critiques the current capitalist system, highlighting its unsustainable consumption patterns and the ecological and social crises it precipitates. It argues for a transition to technocracy, where decision-making is led by scientific experts to address urgent global issues effectively. The potential authoritarian risks of technocracy are acknowledged, with sortition proposed as a mitigative strategy to ensure broader public participation. Ultimately, the document envisions a final evolution into a digital democracy, where enhanced education and technology empower a direct, participatory form of governance that addresses inequalities and promotes cooperative interaction among global citizens.

You must be logged in to post a comment.